Space is like a huge ocean. There is no end to our curiosity about this unknown place. That is why we have been constantly exploring space for life or fuel at different times. Specially designed spaceships are required to reach this place. You have to operate a spacecraft much like a ship at sea. In the event of a shipwreck or boat sinking at sea, passengers can jump into the water and appeal for help. But if a spaceship or spacecraft crashes into the sky outside of Earth, can astronauts jump like those passengers on a ship?

Of course not. Water and space are not one. But what if the spacecraft lacks fuel or electricity? What if it is dilated? Simply put, what would happen to the passengers of a spaceship if something like a shipwreck happened at sea? On the one hand you will lose contact with the earth, on the other hand you will not have enough fuel or oxygen to return to the earth. They will be lost forever.

Nowadays, however, technology has improved a lot. But this was not the case in 1970. As the first two missions of NASA’s Apollo mission were successful, everyone seemed to be becoming very confident. This extra confidence became tomorrow during the Apollo 13 mission. For the first time in space, a spacecraft crashed. However, the team of three astronauts returned to Earth from that state. But how was that possible? If you listen to its explanation, it will feel like a science fiction thriller! It was a successful campaign wrapped in failure. A detailed report on the Apollo 13 mission was published in New Yorker Magazine on November 3, 1982. That report is consistently presented in this book.

Space is like a huge ocean. There is no end to our curiosity about this unknown place. That is why we have been constantly exploring space for life or fuel at different times. Specially designed spaceships are required to reach this place. You have to operate a spacecraft much like a ship at sea. In the event of a shipwreck or boat sinking at sea, passengers can jump into the water and appeal for help. But if a spaceship or spacecraft crashes into the sky outside of Earth, can astronauts jump like those passengers on a ship?

Of course not. Water and space are not one. But what if the spacecraft lacks fuel or electricity? What if it is dilated? Simply put, what would happen to the passengers of a spaceship if something like a shipwreck happened at sea? On the one hand you will lose contact with the earth, on the other hand you will not have enough fuel or oxygen to return to the earth. They will be lost forever.

Nowadays, however, technology has improved a lot. But this was not the case in 1970. As the first two missions of NASA’s Apollo mission were successful, everyone seemed to be becoming very confident. This extra confidence became tomorrow during the Apollo 13 mission. For the first time in space, a spacecraft crashed. However, the team of three astronauts returned to Earth from that state. But how was that possible? If you listen to its explanation, it will feel like a science fiction thriller! It was a successful campaign wrapped in failure. A detailed report on the Apollo 13 mission was published in New Yorker Magazine on November 3, 1982. In this book, the report is presented consecutively on 13 April 1980; A very small flame of light was seen in the far western sky shortly after 9 pm central time on Monday night. It looked like they were expanding somewhere far away from our galaxy. Engineers at the manned spacecraft center near Houston, Texas, also caught sight of the distant sky. They were observing the movement of the Apollo-13 spacecraft that flew two days ago. The spacecraft was then one day away from the moon and was scheduled to land on the moon two days later.

Andy Sullivan, a member of the group of engineers, connected the telescope to the television in such a way that the images visible on the telescope floated on the screen. The night sky above was clear and black like deep water. Sometimes some clouds looked like waves. Neither Sullivan nor his comrades were involved in the Apollo 13 mission. Incidentally was monitoring it for another project related to it. But the spacecraft got lost 250,000 miles away from them.

Whatever they do, they keep an eye on the rocket that is moving the spacecraft forward, which goes out of the Earth’s orbit and leaves the spacecraft and follows the moon behind it. That rocket looked like tiny light particles that vibrated slowly like changing stars. Its edges were shaking as it ran out of fuel. Its brightness was reflected in the different intensities of sunlight. Shortly before nine o’clock, a team of observers on the roof of Houston lost the rocket. With the tools they had, it was possible to observe even those tiny light particles.

Suddenly a bright dot appeared along the middle of the television screen. Within ten minutes it took on the shape of a small disc. The mission control center was 200 yards away from the rooftop observation team. It was a huge building, which was divided into two parts. One part had operation rooms and the other had offices. There was also a connecting part between them. The mission control center had no contact with the monitoring team. Seeing the glimmer of the sky with them, the Apollo spacecraft did not explode or the safety of its crew was in danger. The commander of the crew was Captain James Arthur Lovell Jr. of the US Navy. The pilots of the Command and Lunar modules were John L. Swigart Jr. and Fred W. Hayes Jr. They were both civilian members.

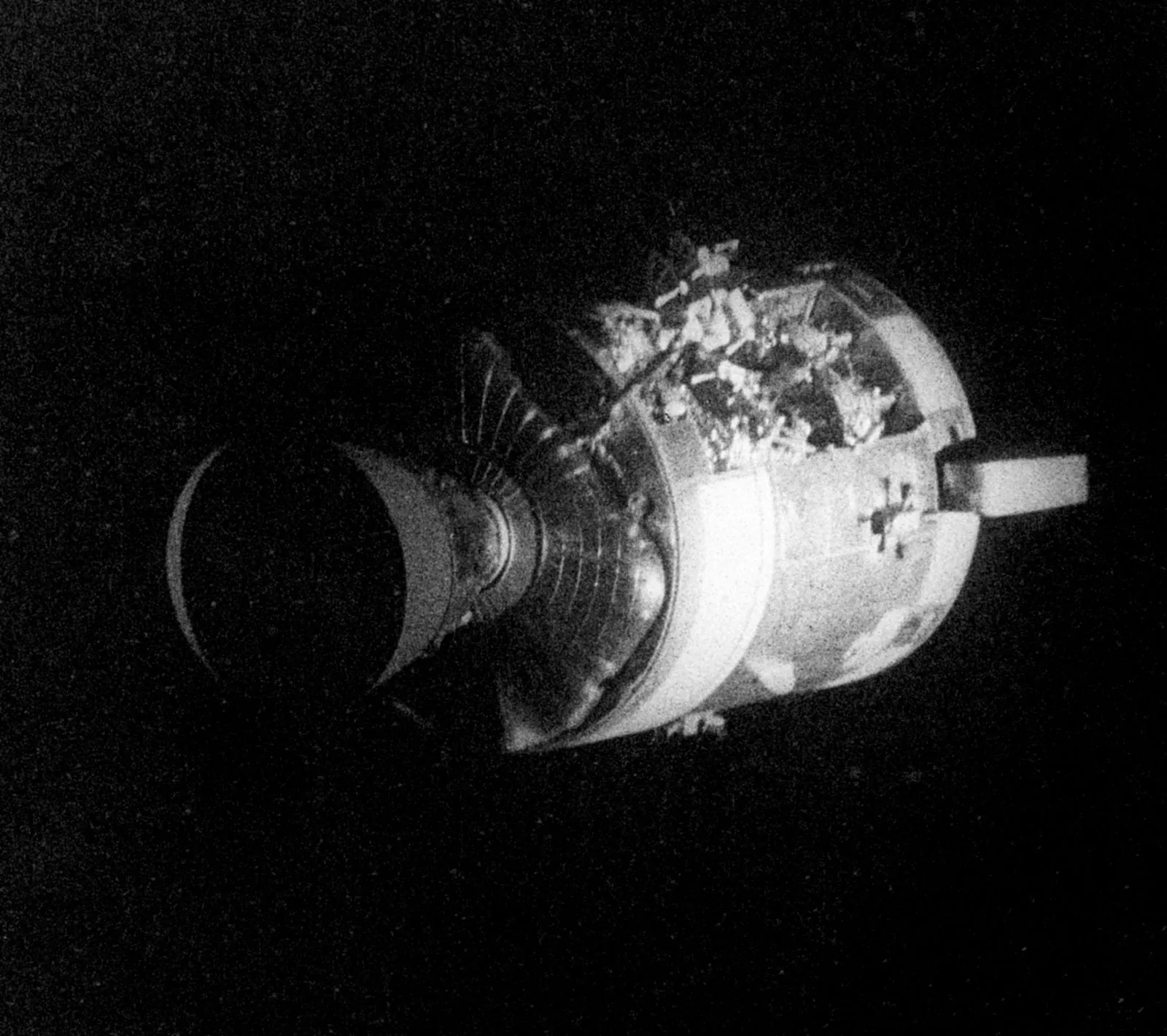

The mission control center could not see Apollo 13 through a telescope. The spacecraft’s two oxygen tanks burst before the center or astronauts could detect them. Then about 300 pounds of liquid oxygen spread into space. As a result, half of the spacecraft’s power and water generation components are lost. Looks like a big lump after the liquid oxygen comes out. In the absence of gravity, these lumps quickly form large fields. When the sun shines on it, it starts to shine. In ten minutes it becomes 30 miles in diameter! Then this white disc slowly disappears. Although some of its remains can be seen an hour later from another powerful Canadian telescope.

Sullivan and his companions thought that the white disc shown on the screen was due to an error in their television set. There was intense shaking and awkward sound on the screen. So they went home and fell asleep and didn’t think about it until the next morning.

Earlier, two more Apollo missions landed successfully on the moon, so no one at the space center thought about the accident. It was later initially explained that the spacecraft may have been hit by a meteorite like Jules Verne’s science fiction. No one thinks there could be a flaw in the spacecraft. Dozens of automatic pens were working at the mission control center, recording the data coming from Apollo-13 via radio waves. The automatic pens were off for about two seconds at the time of the explosion. An error in the electrical system or an error in transporting data from the spacecraft indicates an interruption in data acceptance. But no one noticed it then.

The operation building of the mission control center was like a guttural pillar, like an intelligent creature in a distant space. Flight controllers were isolated from the outside world, like sailors on the lower deck of a ship at sea. Unlike the lower deck, there were no windows. That is, the whole operation building was like the lower deck of a ship. Its upper deck was two hundred thousand miles away in space.

The astronauts are not the only heroes in the secluded area here. Rather they are officers of large ships going abroad. As a result, realizing their role can be difficult for many. The number of astronauts in the spacecraft and the flight controllers at the mission control center combined were equal to the number of officers on the larger ship. They worked together with the sailors called downstairs, just like the officers on the bridge. Even one of the controllers, who was the flight director, could in some cases be considered the actual captain of the spacecraft.

Although the director’s relationship with the astronauts on Earth was interdependent, the astronauts followed his instructions. The astronauts had to rely on them, especially in times of emergency. Even if flight controllers were on Earth, they would receive information via telemetry via radio waves from spacecraft. They had more information about space than astronauts at that moment. The walls of the mission control room on the fourth floor of the operations building were painted gray, like the interior of a command module.

The five large screens in front of the operating room were like space observation windows. The screen in the middle showed the earth on the left and the moon on the right. The dark yellow line in the middle indicates the launch path of the spacecraft.

Most of the flight controllers were in their twenties or thirties. They sat in four rows. At that moment they were carefree, even annoyed. The first 55 hours went by so smoothly that at one point the astronauts sent a message that they were ‘putting the controllers on Earth to sleep’. After the Apollo-13 left Earth orbit, only one incident caught the attention of flight controllers. It was the day before the accident that a small rocket caught fire. Rocket launches were part of a ‘hybrid transfer strategy’. Through this, the spacecraft was sent to the Fra Mauro region of the moon. Incidentally, this paved the way for the spacecraft to return safely to Earth, which was used by previous Apollo missions. If the spacecraft encountered any adversity, it could return to Earth around the moon without adjusting its navigation.

One of the flight controllers is the Retrofire Officer, whose job is to always have a plan in place in case of adverse conditions during space missions, so that the astronauts can be brought back to Earth safely. Two minutes before nine o’clock that night, he informed the flight director that another bridge was about to burn, connected to the console via a pneumatic tube system. He sends out a routine letter, saying that the spacecraft may not be able to reverse its speed and return to Earth if something bad happens.

There were two dozen controllers in charge of the operation room. Only half of those controllers were directly involved in launching a spacecraft at any one time. The front row was called the trench. There were three flight dynamic engineers here. They were in charge of giving directions about the orbit of the spacecraft. Right to left was the Guidance Officer or GUIDO, who was the Chief Navigation Officer, in the middle was the Flight Dynamic Officer or FIDO, who designed the trajectory to see if the spacecraft was following it properly, and to everyone’s left was the retro. Officer or Retro, whose job was to bring the spacecraft back into Earth’s atmosphere.

Most of the staff in the second row behind the trench were systems operations engineers. They monitored the equipment inside the spacecraft. At the heart of this line was EECOM, whose job was to oversee the electrical, environmental and other systems of the command module where the astronauts flew. Beside him was the LM System Officer or TELMU. He did the same thing with the lunar module. With this the astronauts were supposed to land on the moon. Then there were two guidance and navigation control officers. One of them was GNC who was in charge of the command module, the other was the controller who was in charge of the lunar module. They are responsible for providing guidance on the components of the two modules as well as leading the way forward.

To their left was the spacecraft’s correspondent, CAPCOM. He was the only person who could speak directly to the astronauts. To his left was the flight surgeon. The Instrument and Communication Officer was in the third row behind the flight surgeon. He operated radio waves and telemetry transmitters from spacecraft. In the middle of this last row, the flight director used to stay in a convenient place to keep an eye on everyone. He was the co-captain of the terrestrial part of the spacecraft. Administrators and public relations officers sat in the fourth row.

The spacecraft controllers were divided into four groups. Their teams were named White, Black, Maroon and Gold. The White team was in charge at the time of the accident. They kept in touch with each other through intercom. Controllers were abbreviated as Guido, Fido, Retro, etc. Apollo 13 was called only ‘Thirteen’.

On April 13, flight controllers were watching a television show on a large projector screen in their room, half an hour before Soliatis and his colleagues saw the white disc. The show was broadcast by astronauts from a spacecraft. At the time of the accident, none of America’s three major television networks were broadcasting live. Although they were supposed to promote the recorded part later. Television broadcasts were stopped just ten minutes before the accident. If it had continued, the audience might have seen something comparable to any dramatic performance in history.

Flight controllers were leaning back in their chairs and looking at the screen. It seemed to them that the astronauts were happily there. Captain Lavel, 42, was the cameraman and announcer for the Apollo 13 mission. He graduated from Annapolis in 1952. Joined ten years ago as an astronaut. He first turned the camera around and showed the inside of the gray command module. The command module was conical, with a ground diameter of 13 feet and a height of 10.5 feet. It was the equivalent of the inside of a small station wagon. But to the astronauts floating there, it seemed relatively small.

Lavel was resting on the couch in the middle. Beneath it was the service module, which, among other things, had an electrical system, with two large tanks of oxygen in between. The cylindrical service module with the conical command module forms a unit together at one end. Attached in front of these was the lunar module. The total length of the spacecraft stands at 60 feet. Above Lavel’s head was a circular hatch at the top of the cone, through which a narrow tunnel could lead to the lunar module.

Lavel had previously been to space three more times. This was his second trip to the moon. He was previously a member of the Apollo 8 mission to orbit the moon in December 1986. These experiences may have helped him to speak in a poetic manner like a professional presenter. He said

“We plan to show you a space mission today. We will take you from Odyssey to Aquarius through the tunnel. “

Here ‘Odyssey’ was the code name of the command module and ‘Aquarius’ was the code name of the lunar module.

The pilot aimed the camera at the Lavel Lunar module. Hayes was then floating next to the hatch. Lunar was getting ready to operate the module. He, like the others, was surrounded by a white veil. Hayes could not be seen. Because the television relay was not clear. Hayes was a light man from Biloxi, Mississippi, with dark brown hair and a square jaw. He spoke at a slow pace. He joined as an astronaut just four years ago and it was his first mission in space. But he fascinated Lavel and other astronauts on the Apollo 8 mission so much that they named a hole in the moon after him.

You’re in reality a just right webmaster.

The web site loading velocity is incredible. It kind of feels that you are doing any distinctive trick.

Also, the contents are masterwork. you’ve done a fantastic process on this subject!

Similar here: najlepszy sklep and also here: Dobry sklep

Wow, superb blog layout! How long have you ever been blogging for?

you made running a blog look easy. The overall glance of your website is

magnificent, as well as the content! You can see similar here najlepszy sklep